Is the world primed for a new model of global banking?

by Piyush Mathur, Ph.D.

Editorial Precis: Partly based upon his experiences as the administrator of a Facebook group titled Rich People Help Poor People, Dr. Piyush Mathur draws a quick sketch of the global economic desperation that has resulted from the pandemic—and how the strugglers have turned to social media to express their anguish and seek help. He suggests that the foregoing scenario reflects a combination of factors that demands a new model and order of banking. This model, he insists, would have to be a pro-poor, globally oriented banking-cum-aid initiative that would proactively disburse microfinance via remote virtual interfaces and through some type of involvement with social media websites—and without regard to the beneficiaries’ physical location or citizenship.

Let me start out by asking you a few questions:

Do you know of a bank that would allow you to open an account completely online—no matter your citizenship, educational status, or physical location—while knowing that you have no money, and are in fact looking for a small loan or some kind of financial aid?

Do you know of a bank that would do the above while also ensuring that you get to have basic access to the Internet and mobile telephony as part of its financial assistance?

Do you know of a bank that would do all of the above while also keeping its doors open to selling cheap medical, accidental, and life insurance policies online to the global poor?

If you don’t know such a bank, then it is probably for no lack of awareness on your part. Precisely such a bank almost certainly does not exist—and it is not hard to figure out why: Banks are premised upon helping you build wealth based upon your prior wealth; getting you loans and mortgages based upon your credit; and selling you insurance (whenever they happen to be directly involved in that business) based upon your existing and projected incomes. Furthermore, banks cater to geographically ascertainable clients (who preferably own some fixed assets already). Above all, everybody fears losses—and banks are no exception; on the contrary, they epitomize profiteering (perhaps more so now, when governments have made systemic banking unavoidable in all sorts of ways).

The conditions described in the bulleted list up above are thus far from promising to conventional banks; as it happens, they are also not exactly on the banks’ radar. Given that most banks have emerged to serve businesses and individuals of their own regions of origin, they have remained tied to them historically via national politics and law. Prior wealth, evident or perceived socio-legal status, and juridical ties of prospective or actual clients thus remain critically important to most banks.

The foregoing factors have also frequently made banks discriminate unfairly against marginalized groups and individuals inside their own juridico-political territories of operation. As for foreign entities, banks remain suspicious of them (are indeed legally programmed to be suspicious of them); but they welcome (and even woo) them in case these entities’ economic worth is above a certain threshold. Irrespective of their own geographical ties, the super-rich of the world have always had an ease of access to banking facilities.

But banking needs a post-COVID-19 redo—and its unfolding virtualization needs some repurposing, too

Since the popularization of the Internet, banking interfaces have opened themselves up to virtualization. This unfolding virtualization, however, has changed only some of the operational aspects of banking: It was never intended to change its core impulses; and it won’t, in and of itself, do that anyway. But there is something fundamental that could, and should, yet change in banking by dint of virtualization: albeit in response to the immediacy of the pandemic-induced catastrophe comprising unemployment, poverty, starvation, and even other diseases.

According to Oxfam International, by the time we say goodbye to 2020, the world would have seen daily deaths of around 12,000 people “from hunger linked to COVID-19”—a number that might turn out to be greater than the number of those that “will die from the disease itself.” The banking universe—and the governments—must understand that neither conventional aid apparatuses nor lending practices would suffice in the future that is already staring in our faces. While under-addressed, the scenarios of abject poverty and starvation are of course not unknown to the world; we must recognize, however, that what we have now on top of those challenges are the following two items: a fiercely infectious global pandemic, and the availability of a level of technological infrastructure across much of the world.

The point is that the technological infrastructure exists to soften the effect of the pandemic-related physical restrictions on economic activity—and this infrastructure could be used not only to overcome at least some of the limitations of conventional banking but also to articulate and activate as seamless a front against human starvation and economic hopelessness as possible. As it happens, the humanity’s exposure to this technological infrastructure had already substantially altered the culture of mass communication worldwide—and that culture is only going to entrench itself further as the aftermath of the pandemic is encountered. Against the above backdrop, the banking sector must repurpose itself (to some extent) by quickly articulating and implementing a globally proactive micro-finance and soft-loans plan, on the one hand, and by facilitating (if not offering) direct cash aid itself using the social media outlets.

This virtual microfinancial front would have to be proactive in a certain unprecedented sense: Instead of waiting for the desperate to show up at its doorsteps—including virtual portals—the repurposed banking-cum-aid sector would employ (human) social media monitors to keep an eye out for adults around the world looking for small loans and financial assistance necessary for their occupational upkeep, entrepreneurial dreams, and even daily sustenance. Acting somewhat like entrepreneurial headhunters focusing on the global poor, the online agents of this repurposed banking sector would cannily reach out to those seeking small loans or quick financial assistance. Using automated means as well as their general smarts, these online agents would also screen such people on the Internet for their authenticity and merit—and get them funds and some associated help (such as Internet data plans) at the earliest and entirely online based upon some video conferences with them and any other supporting evidence.

It may seem curious to some readers of this essay why Internet data subscriptions, specifically, should even be mentioned as part of a bank loan or financial assistance—when it is assumed that these wannabe borrowers had already been posting on the Internet (and they would have thus been able to afford one data plan or another). I also wondered about that on all those occasions (and there have been many) when I tried to refer financially distressed South Africans I met on Facebook to websites from their own country that I thought would be useful to them. Well, the reason is that there are some countries where people can freely access Facebook (under their government’s arrangement with that company)—but they must pay to an Internet provider in order to access the World Wide Web itself.

Except that many of these people cannot afford Internet services—and they thus cannot access the World Wide Web while being able to surf freely inside the Facebook environment! When they click on an external link that somebody would have shared with them on Facebook, then they see the message displayed here on the right. In other words, many wannabe borrowers of small loans would in fact need access to the World Wide Web before they could even discuss their needs and plans virtually with a bank—unless the bank wouldn’t mind doing all that on Facebook itself!

The need for global, virtual action that would bring together banking and aid; and the rising significance of social media platforms

Here it seems important to reiterate that the conventional socio-economic aid sector—while never a resounding success anyway—cannot continue to be even half as functional as before owing to the nature of this pandemic (and the type of future it has opened up for the humanity). This sector needs intervention from the slightly repurposed banking sector that I have suggested above. At the same time, the aid sector does have socio-economic expertises and knowledges that a repurposed banking order can use (and would have to use)—to stem the sagging fortunes of humans. But the above type of action plan would have to be both global and virtual—even though, of course, it should not aim to outshine the conventional frameworks of economic assistance to the strugglers.

But why is it that a necessarily global action on COVID-19-induced catastrophe is needed? Well, other than the fact that this human catastrophe itself is worldwide—with plenty of economic distress and uncertainty even in the developed world—the local cries for help are increasingly being made on open-ended, internationally exposed virtual platforms on the Internet; and the sectors of banking and aid would ignore them only if they remain brazenly blind to the collective pain of the humanity. A virtual framework for action would, at the very least, serve as an alternative to the conventional, geographically defined banking and aid systems with their physicalist predilections concerning client identification and needs.

We must fully appreciate the fact that the COVID-19 crisis is not only a medical and an occupational catastrophe but that it is also a transportational, communicational, and emotional disaster. Lots and lots of people are not only starving or staring at the prospect of starvation, but they are also being suddenly deprived of the ability to visit their friends; lobby for their causes with the authorities; or freely share their pain with their near and dear ones. The fear of infection, disease, and death is across the board—and it is basically necessary for the safety of all anyway. Under these circumstances, adult humans are left with little choice but to express themselves and seek the necessary help—economic and otherwise—on social media platforms.

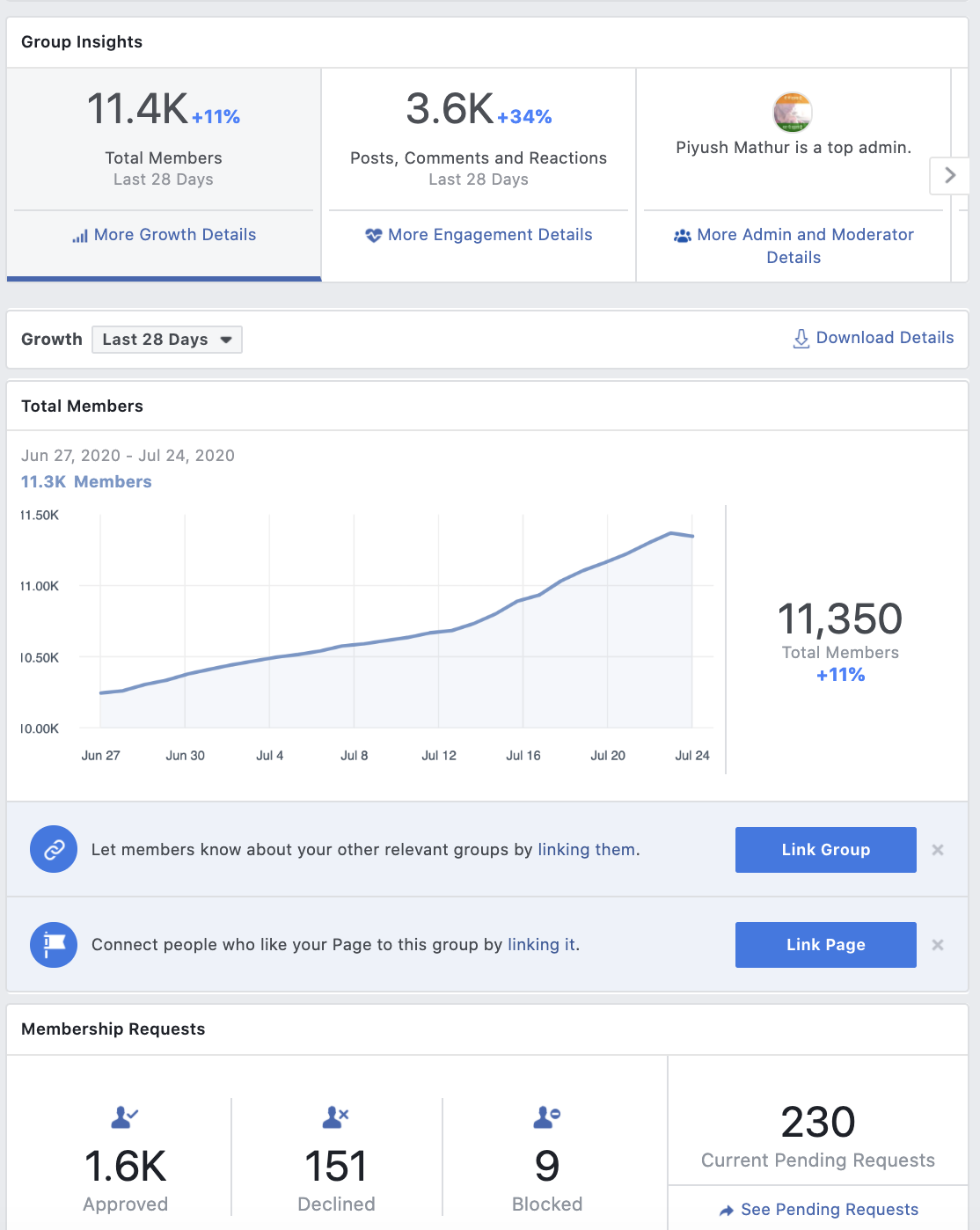

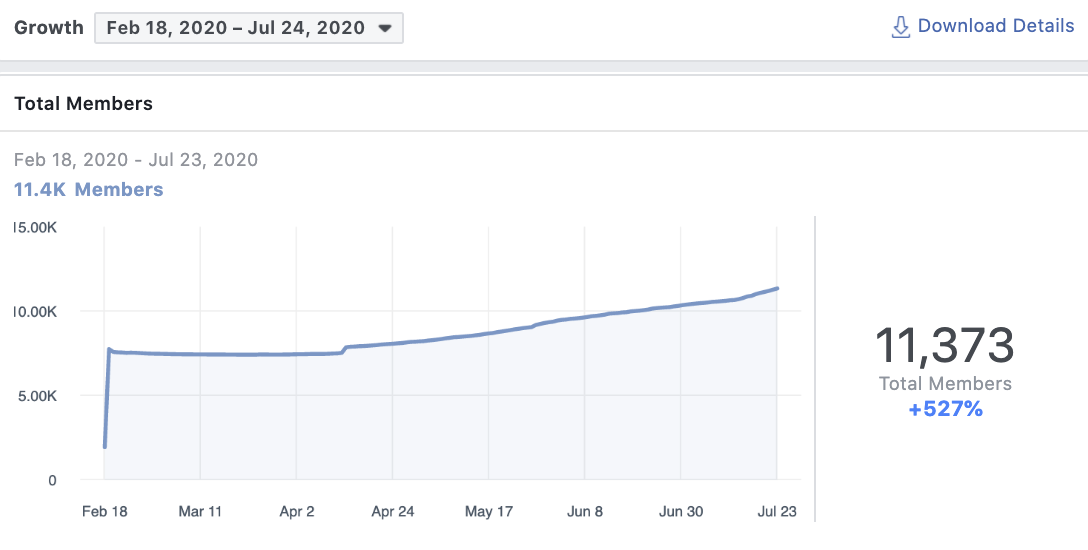

A living proof of the above situation is a Facebook group—titled Rich People Help Poor People—of 11,000 + members that I administer. (On the left of this text, check out the group’s basic details’ snapshot—as on July 25, 2020.) Between February 18 and July 23 this year, this group’s membership swelled by a whopping 527%! (To see that growth rate graphically, check out the other snapshot presented below.) We must remember that COVID-19 news began to trickle out of Wuhan, China in late December, 2019; it would take until around mid-February for the pandemic to get the global masses’ attention—and for it to begin to assume its planetwide shape and size in which we find it today. The swelling numbers of this bluntly titled Facebook group’s membership merely reflect the rise in desperation among the global masses resulting from the pandemic’s coming into its own—just as they reflect the suddenly growing prominence of virtual connectivity for even those whose occupations had had little to do with it.

Rich People Help Poor People: A 527% growth in membership between February 18 & July 23, 2020

Leave aside the inference drawn from the recent spurt in the group’s membership numbers, most pleas for help posted on the group’s discussion page cite COVID-19-related restrictions as the prime cause for job loss, poverty, and a gloomy outlook. Everyday the group has scores of such evidence-backed pleas—made by people from all over the world, including the US and the UK—even though a ridiculously small number of them get any support from the “rich” people that have also happened to join the group. Many of these pleas are for small loans, say, to help start a new business or replace a faulty equipment; most of them are for direct help of very small amounts (say for a family lunch, diapers, bus fare, and so on)—even though lack of employment remains the prime reason behind these latter types of pleas, too.

The Zidisha precedent—and its limitations

One may wonder why these people are not going to their local authorities or banks for this sort of help. The immediate answer to that question is that COVID-19 has slowed down bureaucracies even more than their usual; and it has also prevented people from visiting offices and filling out forms, etc. But of course a long view would easily suggest that local authorities and banks around the world have only occasionally been a success story as far as helping out the needy is concerned.

Indeed, this was the scenario that so pained Julia Kurnia—while she was on a visit to Niger in 2008—that she ended up founding Zidisha Incorporated, a nonprofit microcredit agency headquartered in the US state of Virginia. Kurnia’s stated aim behind starting this project was to use the Internet to make “geography irrelevant” to securing loans, whereby “place of birth” won’t inhibit “our members' ambitions.” Unfortunately, though, the Zidisha approach cannot be said to have captured the mainstream banking’s imagination—despite the fact that online banking has otherwise seen a steady rise.

Moreover, the Zidisha approach itself appears to be not proactive or comprehensive enough for the kind of action, I feel, we now need internationally in the wake of the pandemic. The foregoing is not at all meant as a criticism of Zidisha; it is more of a lament that we have not only not learnt from Zidisha but have also failed to build upon its early initiative in the right direction. Nevertheless, I shall discuss Zidisha briefly—and highlight why it should not suffice anymore.

The Zidisha model rests upon an entrepreneur’s applying to the agency via its own Internet portal for a loan; his or her application’s being screened for viability by a wannabe investor (presumably from the industrialized world); and the investor’s sanction of a personal loan, along a peer-to-peer network, to the applicant-borrower toward his or her project. Once this borrower has met the project’s target, he or she is expected to refund the loan amount to the investor, who is then expected to re-invest the same amount into another viable borrower's project.

A key underlying limitation of this model is that it expects an entrepreneur to know about Zidisha (and to make an application to the agency based upon that awareness). I consider the above a limitation because Zidisha (founded in October 2009) remains an obscure agency to date despite the press coverage it has received from some reputable news outlets. Even media junkies—leave aside economic strugglers and wannabe entrepreneurs—of the world would not have heard of it. Given this situation, Zidisha’s cannot be considered an outreach effort for real; besides, as of 2020, it also seems a bit technologically outdated in connection with its lack of an aggressive outreach programme.

The pandemic-induced mass desperation—against the backdrop of the rapid worldwide expansion of the Internet lately and advancements within associated virtual technologies—asks for an even more radical (and yet humane) intervention on the part of the banking sector than what the Zidisha model has happened to offer. Banks must proactively approach (on the Internet, especially on social media) wannabe entrepreneurs and occupational re-toolers in distress—something that Zidisha does not do; and they must liaison with social media influencers (even small timers such as myself) as well as social media companies themselves as part of their outreach. Moreover, the conventional North-South Divide has just a little less to do now with the international political borders than with region-wide and/or individualistic economic limitations: There is plenty of poverty and deprivation in the United States itself; and there is nothing to suggest that the same banks should not reach out to the poor of the richer world.

We will also need holistic online mentors—as part of post-COVID-19 banking intervention globally

I understand that what I have suggested above is very counterintuitive—in that investors (leave aside banks) do not like to approach strugglers looking for investment loans. But we must remember that the popular banking/lending paradigm is fundamentally elite; it is also presumptuous in favour of the formally educated (and fluent in certain languages). These peculiarities of the popular banking paradigm also make it unsuited to address the pains of this planet-wide pandemic.

Nevertheless, this same banking sector would yet have to be enlisted to address those very pains, given that other institutions are even less equipped to address them for other reasons! So, in order to make themselves more suitable for handling the unfolding grassroots global crisis, the banks themselves must retool, as it were: They must include a mentorship and expertise-sharing dimension to their global lending outreach. They do not necessarily need to have an endless range of mentors and experts on their payrolls to accomplish the above; what they would need to have onboard is a small team of predominantly Humanities-educated, Internet-alert, social media savvy individuals that could quickly put together useful packages of information—including pre-existing expert presentations—relevant to a wannabe entrepreneur’s or retooler’s project; and connect these entrepreneurs/retoolers to any pro-bono or low-cost external advisors interested in their specific projects.

In fact, Facebook—though not exactly a bank—has already put in place a pilot programme involving online mentorship (even though it appears to be different than what I have suggested above). Indeed, following its offer to me—as the administrator of Rich People Help Poor People—I have also signed on to that pilot programme very recently (but am still awaiting on the company’s follow-up on it). Banks can thus choose to learn from Facebook, for example; or they may simply collaborate with it.

Most often these wannabe entrepreneurs or retoolers expressing their economic requirements on random virtual platforms won’t need any guidance or mentorship; however, a general need for emotional and intellectual companionship and mentorship cannot be underestimated: even, I daresay, on the part of blue collar entrepreneurs from the Global South! At any rate, wannabe entrepreneurs or retoolers looking for economic support on social media sites—my experience from my Facebook group suggests—do appear to see much merit even in mere kind words that a stranger could offer from thousands of miles away.

All of that is fine and dandy—but how could a bank reclaim its loans from these random virtual borrowers from all corners of the world?

I am sure that many readers are preoccupied by the fact that online scammers would love to take advantage of this grassroots-inclined, pandemic-induced global order of virtual banking that I have daydreamed about. It is indeed true that spammers and scammers—both big and small, clever and not-so-clever, plague the virtual sphere; there is hardly a day when I do not remove around 15 of them from my Facebook group—whose title makes it a magnet for those trying to make a fast buck out of thin air. Ergo, and given my limited understanding of fintech, I was also initially apprehensive of the viability of screening and tracking borrowers completely online.

However, speaking in a personal capacity, Chris Humphrey—a project manager for a values-based bank in the UK, and the founder of Jobs on Toast—convinced me that the contemporary banking sector has the technological knowhow and infrastructure relevant to identifying and tracking people virtually. Humphrey seemed more concerned about how a bank would interact completely online with the projected diversity of the (global) unemployed, wannabe entrepreneurs or retoolers—with their varying degrees of literacy, education (coupled with their cultural differences, multifarious skills sets, and linguistic competencies), etc. I did completely share Humphrey’s apprehensions—though it seems to me that engineers should be able to address some of these issues algorithmically and via artificial intelligence and facial recognition mechanisms.

Of course those steps themselves would raise fresh ethical concerns: but humans have more immediate ones now that we must first address. And yet, there is something else that I shared even more with Humphrey: His instinctive characterization of the challenge of diversity among global virtual wannabe borrowers and financially distressed people as "an interesting problem.” I certainly believe that curious minds of today cannot help but consider this situation as exceedingly worthy of their intellectual investments—and I would like to collaborate with them if an opportunity to do so arises.

Meanwhile, although Humphrey could not promise—and could not have immediately promised anyway—any action in the desired direction, I thought it worthwhile to share my ideas here with the wider world. For as interesting as this problem is from a philosophical, analytical, and managerial perspective, underneath all that are cries of desperation and dark hopelessness for the strugglers. One might go so far as to suggest that a comprehensive virtual outreach of the financial and humanitarian variety to the pandemic-stricken strugglers of the world might just be the challenge for the next 25 years anyway—and it would require some sort of a globalistic merger of banking, socio-economic aid, and social media. I would like to be part of a response to this gargantuan ask—and so should you!

Piyush Mathur is the author of Technological Forms and Ecological Communication: A Theoretical Heuristic (Lexington Books, 2017). His other academic publications could be accessed here. He can be contacted here.