When prisoners speak out

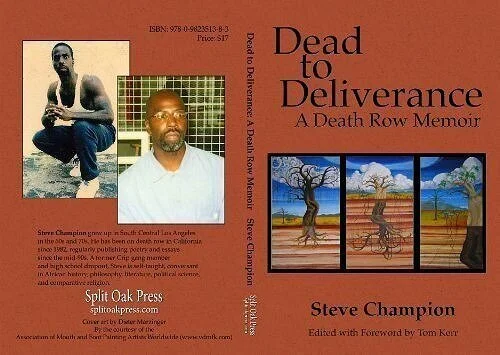

A retro-review essay on Steve Champion’s Dead to Deliverance: A Death Row Memoir (edited with Foreword by Tom Kerr) (Split Oak Press, 2010)

by Piyush Mathur

In 2018, the world saw the least number of “known” executions since 2009—except that country-specific trends had not been consistent during the same period (and 2019 did not turn out to be a consistent year in that regard, either). Meanwhile, even though the DRC, Fiji, Madagascar, Suriname, Benin, Nauru, and Guinea abolished capital punishment through 2015-2017, there have also been renewed calls favouring it in Sri Lanka, Turkey, Russia, the Philippines, and South Africa. A real issue is that China, India, US, and Indonesia—which altogether house the majority of the global population—have not changed their position on capital punishment: They continue to practise it.

In fact, there has lately been a surge of support for capital punishment in India—reflected in the passage in 2013 of the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, which extends the provision of capital punishment to rapists. The United States also saw an approximately 5% rise in the public support for capital punishment between 2016 and 2018—and the Trump administration has lately been trying to reinstate the federal death penalty. In the last days of 2019, China, Saudi Arabia, and Japan grabbed the international headlines for their executions; however, the dismal, fractured state of Brexit-Trumpist politics had otherwise forced the world to focus on a lot of other issues throughout the year and even prior.

The global civil society’s prime preoccupations lately appear to be these: the chauvinistic anti-politics of identities and strident nationalistic agendas; climate change; sexual abuse (especially of women, and of the religious inside the Christian establishment); terrorism; unending wars in parts of the world; and refugees. Through the maze of the above issues, the topic of capital punishment showed up only sporadically in the international media—even as extrajudicial executions at the hands of certain terrorist organizations, drug cartels, and (in some cases) governments overshadowed even that coverage.

But with the Trump administration’s ongoing attempts at reinstating capital punishment at the federal level, this topic is very likely to figure in the upcoming US presidential election, just the same; and given that US presidential elections are closely watched the world over, they would have a spillover effect globally. Through the presidential campaign, political references to the death penalty would likely come tied to a broader discussion on social justice, criminal defence, and the status of minorities in the US—given that attitudes toward capital punishment vary domestically (based, to some extent, upon one’s ethnic background). According to a 2018 report generated by the Pew Research Center, “[a] 59% majority of whites favor the death penalty for those convicted of murder, compared with 47% of Hispanics and 36% of blacks.”

At any rate, members of the global civil society should ensure that the focus on the death penalty, social justice, and prison reform is not only kept alive but is also continued to be deeply explored. To that end, I thought it worthwhile to take the readers of Thoughtfox back to a decade-old American publication—Steve Champion’s book titled Dead to Deliverance: A Death Row Memoir. As its subtitle suggests, this book is an autobiographical account of an inmate under a death sentence.

While the broader issues raised in it seem all the more pressing now in the US and elsewhere than they were in 2010 (when it was published), the book also deserves to have its decennial anniversary be celebrated. Champion wrote this book while awaiting his execution at San Quentin, California. He was sentenced to death in 1982—when he was only 18—for two counts of murder in the conduct of a robbery; in the same case, a co-defendant was also found guilty for the same crimes. Champion has always maintained his innocence—and he remains on the death row; his federal appeals to revoke his death sentence are not yet exhausted.

Dead to Deliverance: A Death Row Memoir (2010)

For those who keep themselves abreast of the American penal system, this book’s factual details as well as its subtext—of gang and prison lives— would seem more or less familiar. What is unusual about this account is that it is an inmate’s own tale about prison life—and whatever would lead him to it starting out as a 5-year old who beat up another kid on his eldest brother’s order. This is a critically reflective tale—in which the concrete flows into the abstract; passion communes with understanding; and prison/gang talk intermixes with eclectic scholarly references. Most important, this book is an inspiring allegory of zealous learning and attainment of mental freedom—freedom from ignorance/prejudice/limitations—both on the part of its author and its editor.

“Every person has his own history full of blank pages that have yet to be filled.” — Steve Champion

The book’s editor, Tom Kerr, is an Associate Professor of Writing at Ithaca College, New York; he was my pedagogical mentor at Virginia Tech and has since been a close friend of mine. This book came out of a writing seminar he taught in 2003. The seminar included correspondence between his students and prisoners “interested in sharing their thoughts on the U.S. Prison Industrial Complex (PIC).” So, aside from being its author’s memoir, Dead to Deliverance is also its editor’s labour of love—as Kerr had to spend considerable time and energy on this project, for both editorial and logistical-cum-bureaucratic reasons.

But the book is also an attempt by two Americans at bridging a combinatorial divide of physiognomy and economic class in their beloved nation-state. Kerr was driven to this project by a deep sense of responsibility toward fellow Americans that have not had the privileges that he claims he has had as a White American male belonging to an upper-middle class family; Champion, an Afro-American, was born into and grew up in deprivation and crime culminating in his death sentence. “While Steve [Champion] was negotiating the unforgiving, hard-scrabble streets of Los Angeles without guidance from his absent father,” Kerr points out,

I was playing tennis, golfing, and swimming at the Colorado country club my father [had] joined for the benefit of his family…I was afraid of the black kids who lived on the other side of that divide, then 32nd Avenue, now Martin Luther King Boulevard, and my friends and I studiously avoided black neighborhoods.

While Kerr has had to break out of his shell of privileged ignorance he was born into through self-education, college teaching, and by reaching out to the less privileged, Champion has had to educate himself for self-enlightenment as well as self-empowerment. Like Kerr, Champion has not restricted himself to promoting his narrow self-interest: far from it, in fact. Given that Champion cannot legally communicate to the public about his own death sentence as his federal appeals are ongoing, he has tried to oppose capital punishment generally—especially by writing to media outlets about difficult issues related to justice.

Kerr’s case against capital punishment—and for transparency and restorative justice

In the Foreword, Kerr makes an assiduous, multilayered case against the death penalty—arguing that a society renders itself fundamentally unhealthier if it continues to retain capital punishment: the epitome of punitive measures. He observes that it is only an aggressively prosecutorial society unwilling to accept its responsibility in producing crime and criminals that could condemn its own to death—in an environment where prisoners, in any case, are kept outside the public view and have their voices muffled.

Directing the reader’s attention to the mutability of human existence, Kerr exposes how society errs if it forgets or chooses to neglect that factor: “We know that we are more than what we do in a given moment or period of our lives; however, criminal conviction, especially when it comes to violent crime, encourages our natural tendency to stereotype and consequently, to dismiss a person based on past actions.” Although not a practicing Christian (in any popular or conventional sense of the term anyway), Kerr stresses “forgiveness and redemption”—“two central tenets of Christian morality”—to highlight the significance of being able to “distinguish the act from the actor, to condemn bad acts while forgiving the people who commit them.”

Contrasting two cases in which clemency was denied by George W. Bush and Arnold Schwarzenegger—respectively to Karla Faye Tucker, who had confessed her guilt, and to Stanley Tookie Williams, who never confessed—Kerr highlights the actual irrelevance of confession, apology, or atonement to the political decision of denying or granting clemency. All of the above, Kerr argues, is on top of the narrowly legalistic fact that “as the Innocence Project proves, we regularly find that convicted killers and others are indeed innocent, despite the ‘overwhelming evidence’ of guilt presented at their trials.”

To the conventional bureaucratic argument that outsiders are poorly positioned to fathom the pressing needs of prison administration—needs that presumably require strict measures of isolation, censor, control, surveillance, discipline, and punish—Kerr responds by deeming the prisons’ lack of transparency itself as the culprit, as a hindrance for the public to accurately understand and assess those measures. Going further, he deems this lack of transparency as “an offense to human rights.”

On the broadest level, Kerr strongly proposes what has been termed as “restorative justice”—which

as distinguished from our current model of retributive, punishing justice, requires that we always allow for the possibility of redemption, of the return of the offender to constructive relations with the offended.

A brief on the memoir

I am sparing my words on the memoir itself because I believe that the readers should read it directly—as I won’t be able to do justice to Champion’s writing: It is sprawling yet intimate; mature yet youthful; philosophical yet down-to-earth; and full of energy that only specific slangs, lingoes, and jargons could retain. Plus, there is a very strong story element to his narrative that deserves to be enjoyed like a novel—and not merely to be learnt from. Nevertheless a brief sketch of his account would be in order.

Champion starts out from his early childhood. He tells us how his mother mostly single-handedly raised a family of eight; how he found himself growing in an environment in which crime and jail were not unexpected experiences, even though his mother was a pious Christian who would remain unaware of how her son was getting deeper into street life. The account leads up to how, in the 1970s, he joined the dreaded black-youth gang called “The Crips.”

Champion provides concrete stories from his life as a Crip—all the way up to how he began to get in and out of prison before being sentenced to death and having to wait for that sentence to be executed. He details how he adjusted to prison life and also evolved as an inmate. Highlighting instances of how administrations have, over the course of more than two decades, used and abused San Quentin prisoners—such as by inducing those mentally challenged to make their fellow inmates’ lives miserable—he also fleshes out what it means for anybody to be imprisoned; he also devotes one chapter to the routine of a typical execution day.

The book’s longest chapter, which is also the last (and which ends in a poem) is titled “Connection and Collaboration: On Becoming a Writer in Prison.” I personally consider this chapter to be the most inspiring. Yet, it is a prior chapter that has perhaps the most quotable sentence: “Every person has his own history full of blank pages that have yet to be filled.”

That chapter is titled “I Dream the Same Dream Everyday.”

— - —

External references & background material

Stubbs, Cassandra (December 13, 2019) “The death penalty in 2019: a year of incredible progress, marred by unconscionable executions” American Civil Liberties Union: https://www.aclu.org/news/capital-punishment/the-death-penalty-in-2019-a-year-of-incredible-progress-marred-by-unconscionable-executions/

Amnesty International (2019) Amnesty International Global Report: Death Sentences and Executions 2018: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ACT5098702019ENGLISH.PDF

BBC (December 21, 2019) “Why is India passing more death sentences?”: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-50811366

Businesstech (September 3, 2019): https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/338473/south-africans-are-calling-for-the-death-penalty-to-be-reinstated-heres-what-government-says/

CNN Wire (December 17, 2019): "Use of death penalty in US this year was ‘near historic lows,’ report says": https://fox43.com/2019/12/17/use-of-death-penalty-in-us-this-year-was-near-https://fox43.com/2019/12/17/use-of-death-penalty-in-us-this-year-was-near-historic-lows-report-says/

Esguerra, Christian V. (July 26, 2019) “Duterte warned vs ‘political cost’ of reviving death penalty” ABS-CBN News: https://news.abs-cbn.com/video/news/07/26/19/human-rights-watch-ph-to-pay-political-price-if-death-penalty-is-restored

Ithaca College: https://faculty.ithaca.edu/tkerr/

Lynch, Sarah N. (July 25, 2019) “U.S. Justice Department resumes use of death penalty, schedules five executions” Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-justice-death-penalty/u-s-justice-department-resumes-use-of-the-death-penalty-schedules-five-executions-idUSKCN1UK258

Morales, Neil Jerome & Martin Petty (September 9, 2019) “Shoot them? Hang them? - Filipino heavyweights hanker for death penalty return” Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-deathpenalty/shoot-them-hang-them-filipino-heavyweights-hanker-for-death-penalty-return-idUSKCN1VU0UZ

Oliphant, J. Baxter (June 11, 2018) “Public support for the death penalty ticks up”: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/11/us-support-for-death-penalty-ticks-up-2018/

Philippine Daily Inquirer (July 28, 2019) “Death Penalty Enthusiasts”: https://opinion.inquirer.net/122907/death-penalty-enthusiasts

RT (October 13, 2019) “Russians want return of DEATH PENALTY after brutal murder of 9yo girl”: https://www.rt.com/news/470818-russia-death-penalty-child-murder/

San Quentin Death Row Artists & Writers: https://www.artofsanquentin.com/steve-champion-adisa-kamara.html

Söğüt, Mine (September 2, 2019) “Who stands to gain if Turkey restores death penalty” Worldcrunch (CUMHURIYET): https://www.worldcrunch.com/opinion-analysis/who-stands-to-gain-if-turkey-restores-death-penalty

Champion, Steve (2010) Dead to Deliverance: A Death Row Memoir (edited with Foreword by Tom Kerr) (Split Oak Press). ISBN-10: 0982351380. ISBN-13: 978-0982351383. Price USD 17. Pages: 230.

Piyush Mathur is the author of Technological Forms and Ecological Communication: A Theoretical Heuristic (Lexington Books, 2017).