Ribeiro letter controversy reflects a deepening rot in India's governance—but a lot else, too

by Piyush Mathur

Editorial note: We thank Dr. Manisha Gangahar for availing Thoughtfox a copy of the statement that the 26 retired police officers sent to the commissioner of Delhi Police as well as their list of names. These documents—hitherto unavailable on other media reports—can be downloaded as pdf files via appropriate links in this article.

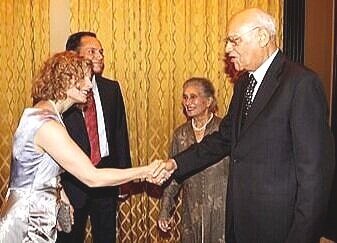

August 26, 2011: Julio Ribeiro is being welcomed to the U.S. National Day Celebrations organized by the U.S. Consulate Mumbai at Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, Mumbai (Photo credit: American Center, Mumbai)

Bearing “a heavy heart,” Julio Francis Ribeiro—a well-known retiree from the elite Indian Police Service (IPS)—wrote a letter on September 12 to the Indian capital’s police commissioner requesting him to “ensure a fair probe” into the seven hundred and fifty three (753) cases that the police has filed there in the wake of the so-called North East Delhi Riots of late February. Played out between irreligious idolators and Muslims, these riots had evolved out of an ongoing protest in Delhi against a rise in systemic prejudice against the Muslims—most recently reflected in the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 and the governmental steps taken in regard to the National Population Register (NPR) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

During those protests and riots, Delhi Police’s prejudicial stance was frequently on display in front of the cameras—whenever it was possible for the people and mediapersons to use them—and surely it was reported to have been there aplenty offscreen. Ribeiro’s letter underlines the police’s prejudice in the more serious stage of its involvement: It filed reports “against peaceful protestors” but “deliberately failed to register cognizable offences against those who [had] made hate speeches” instigating the riots. Here, Ribeiro mentions the names of Kapil Mishra, Anurag Thakur, and Parvesh Verma—politicians belonging to the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), which rules the Centre and favours an aggressively nationalistic segment of India’s idolatrous pagans.

While Mishra had threatened the police of removing the (Muslim) protesters with the help of his supporters unless it did so itself, Thakur had called the protesters “traitors”—leading a chant in which his supporters shouted back that these rascals be shot. As for Verma, his speeches ensured the public that all Delhi mosques that had been built on the public property would be removed if the BJP came to power in the state in the upcoming election on February 8. (The BJP would end up losing the election by an embarrassingly wide margin.)

Nothing that Ribeiro has mentioned in his letter is unknown to those who keep up with India’s media at all (whether they agree on the facts or their interpretations is another matter). In many ways, the content of Ribeiro’s letter—while exceedingly welcome to those who care about truth and fairness—would have been unremarkable on its own. Even the fact that Ribeiro wrote a letter raising an issue of public interest is nothing unusual, given that during his retirement years he has written other such—journalistically reported—letters of public interest to the authorities or the media. But there are additional factors now—some of which remain in the background—that have made his this particular epistolary exercise rather remarkable and newsworthy.

The overriding factor is simply that nobody is supposed to contradict the state authorities anymore, pretty much anywhere in India (no matter whether it is a BJP-ruled state or a Mamata Banerjee-ruled state)—inasmuch as India’s mainstream political environment has become polemically too nationalistic (veering toward totalitarian) under the cult of Modi. That sort of a claim may be viewed to be absurd—given that the Ribeiro controversy is directly linked to a long protest, and the related riots, in Delhi; moreover, the Modi rule so far has hardly seen a moment of true civic peace, marred as it has been by a stream of protests, riots, attacks, and whatnot: invariably as a reaction against one (prejudicial) state action or another.

But that’s the whole point: Prospects for civic dialogue have basically been sucked out of the entire political-cum-bureaucratic culture of the country, even as the quality of all institutions—from the universities to the courts to the media to the civil services to the police—has been made to take a sharp fall via illicit political interference and tone-deaf administrators. In a country that was never substantively democratic—and where most state functionaries have always acted as omniscient, corrupt overlords to the average citizens—where was the scope for institutional decline? And yet, miraculously, that’s what the ruling coalition has come to effect.

As dissent from the central government’s poorly articulated and whimsically implemented policies is persecuted by the authorities or dominant sections of the media, dissatisfied citizens at large are left with only one real choice: come out into the streets and protest! Needless to say, this riles the authorities even more—as they know that their only real priority is to keep their political bosses in excellent humour—and they implement the ruling coalition’s ideological biases through police action and other indirect forms of intimidation. One does not need to mark a dissent from policy, even; public displays of mere personality differences from the extended aura of the Prime Minister are enough to invite social or media persecution, and even legal prosecution.

All of that is happening insofar as the central governmental machinery is being made to dance a bit too precisely to the nationalistic whims of the BJP, which is determined to expand its political control across the country no matter what the costs (say, even if it means for the BJP to cherry-pick its own stated ideals). Poaching politicians—even its own erstwhile bitterest critics—from its conventionally rival parties is routine for the BJP now; all that the party cares about is winning the next election, in one state/locality or another, while trumpeting its idolatrous nationalism of Hindutva anyway. The party somehow did not even need to convince its followers of the suitability of the above strategy—as they seemed, for the most part, to have already been on board; in any case, there would have been no other way available for the BJP to expand its capture of power in an impatient order.

Against the above backdrop, non-BJP provincial rulers remain on edge; have hardened their own stances vis-a-vis the Centre; and they remain preoccupied with keeping their regional bureaucracies fiercely loyal to themselves and their own parties—sometimes at the expense of the quality of their own administrative services to their local publics. That would be another way to say that non-BJP provincial parties and their leaders cannot help but mirror, at least to some extent, the BJP’s own strategy nationwide—never mind their ideological differences. When breathing outside a state ruled by the BJP or BJP-affiliates, the Indian citizen thus tends to get squeezed between the Devil and the Deep Sea: a nationalistic-authoritarian-totalitarian central government and an edgy provincial fiefdom (each of them being democratically elected otherwise).

Neither of these two entities is in any mood for dialogue with the other, of course; but the worst part is that the average citizen is, in most cases, nowhere near the priority of either on a day to day basis. It is usually only a few months preceding an important election that the Indian citizen is appealed to en masse via blatantly categorical sops; a parallel attempt is made to scare an ideologically invoked collective of voters to elect this or that candidate. The North East Delhi riots were merely one such instance, given that the Delhi assembly polls were quite explicitly the motivation behind the hate speeches that Ribeiro cites in his letter.

When inside a BJP or BJP-affiliate-ruled state, the Indian citizen must keep his lips stretched from ear to ear or invite the accusation of being an anti-national element, maybe even a traitor; if (s)he dares to do otherwise, then (s)he may be persecuted online, offline, or via frivolous complaints to the police or a court of law. Owing to political considerations, the police tends to take such frivolous complaints way more seriously than genuine pleas for help; and of course, once such a complaint has been filed and action on it initiated, the accused’s state-led harassment has begun. As for the courts, all that truly matters is the whim of a particular judge or bench of judges rather than any clear, well-reasoned law—which India does not quite have when it comes to freedom of expression (and most Indians fundamentally lack an appreciation of that concept, partly because they remain trapped inside a convoluted British-colonial legal heritage).

Very little of the above circumstances overall is unprecedented in India—a fact that serves as a charming, recurring alibi of sorts for the ruling coalition. The ruling coalition’s references to Indira Gandhi’s Emergency (1975-1977) as the pinnacle of repression in independent India are routine and, in many ways, justifiable. And yet, we must remember that a formal declaration—say of Emergency—is hardly the prerequisite to running a propagandist, repressive government. In the present times, it may in fact be strategically convenient in India to not formally declare authoritarian rule while trying to have it anyway.

The nation-state of India does appear to be under such an unformalized, undeclared authoritarian rule that is strategically suboptimal in its totalitarian aspirations. But unlike during the Emergency, the country’s bureaucracy is no more “efficient” in delivering its services to the citizens than at any time earlier; in fact, it may only be less efficient now than through the concluding years of Manmohan Singh’s prime ministership. The circumstances are not ripe yet for a totalitarian government in the proper; and such circumstances may not present themselves in India anytime soon anyway. And yet this awareness itself, the BJP realizes, could be used as an alibi, even an important advertising tool, for continuing an operationally whimsical, legally convoluted, yet predictably discriminatory form of nationalistic authoritarianism—so long it is able to tout it as the best in democratic governance that the country has ever had!

In this scenario, the BJP remains immensely lucky given that the key oppositional party at the Centre—the INC—is utterly unfit to shine a light on any democratic ideals given that it remains internally a Gandhi-family fiefdom, which is only going deeper in that adverse direction. The rest of the opposition, for the most part, is nothing if not a floundering patchwork of similar dynastic organizations with plenty of casteist rhetoric about equity and empowerment—ironically marketed as some kind of an anti-casteist movement. A key result of the above situation generally is that all governmental institutions, organizations, and fraternities have become supremely touchy about any criticism that might come near them; overly broad, collectivist notions about prestige and status now pervade the government’s organizational rhetoric.

Forget about internal whistleblowing—which would be tantamount to acting as an organizational traitor anyway—even an external point of objection against anything critical about some aspect or functionary of one’s own professional fraternity now causes a massive organizational heartburn. Expressions of such organizational/fraternal heartburns come pre-aligned with the government’s agenda; and it is always a good bet that they are ploys of the organizational leaders to remain in the good books of the political bosses—be it at the Centre or at the level of the state. In many cases, such expressions of organizational/fraternal heartburn are the de facto stepping stones for the organizational/fraternal leaders toward positions of direct or indirect political power for themselves.

Under these circumstances, voices of genuine critique remain quite unwelcome—and self-critique would be a distinctly rare bird. As it happens, Ribeiro’s letter is both an external critique—of Delhi Police (and, by extension, of the IPS itself), for which he does not work—and a self-critique, given that he is a retired IPS officer. In today’s India, his letter is thus the equivalent of a double fault in tennis! Little wonder, then, that it got so much media attention as it did—followed as it was by a letter of support (released on September 14) by nine other former IPS officers; and what with these two letters themselves having been rubbished by a statement sent to Delhi’s police commissioner (on September 18) by 26 other retired IPS officers.

With Ribeiro’s having come to limelight as Director General of Punjab Police in the 1980s for his tough stance against Sikh militants—in a policy called “bullet for bullet” by Arun Nehru—nobody can question his patriotism in today’s hyperweather. Moreover, before being conferred the 3rd highest civilian honour of the Padma Bhushan by the Government of India in 1987, he had been “awarded the President's Police Medal for meritorious service in 1972 and the President's Medal for distinguished service in 1978” (Vaz, 1997). So, both nationalistically and organizationally, Ribeiro is no ordinary retired IPS officer—and nor did he ever have political aspirations (which otherwise abound among contemporary IPS officers).

The fraternal heartburn that the other 26 IPS officers have felt is thus pretty intense—and yet, their statement expressing the same remains fundamentally confused about the meaning of the word “right;” worse, it remains completely oblivious to the amount of suffering that the average citizen of India goes through while interacting with a government office to get anything done, leave aside while interacting as an accused with the police and the court system. Their statement asserts that former officers like Ribeiro “have no right to suspect or question the integrity and professionalism of their successors in the Indian Police Service, and in turn demoralise them.” But surely everybody has the right, we all know, to question the police!

Elsewhere, referring to those against whom police complaints have been filed, the same statement says the following:

The Delhi Police has every right and duty to investigate…and custodial investigation is a part of due process of law. The accused has his rights under the law to seek anticipatory bail or regular bail… and the right to a fair trial where he can prove himself innocent.

But that type of an assertion raises the following question about its 26 writers’ wits: Do they seriously believe that Ribeiro does not know all that? But of course, they believe otherwise—since their own statement says previously that Ribeiro “and his associates…very well know that there is a due process of law, and there is no one above the law.” And yet we all also realize that Ribeiro also knows—rather intimately, as he must—that police investigations can be prejudicial from the get-go—and that under such circumstances, the accused is already a victim of governmental or police prejudice and exploitation (even as there might be other persons that would have deserved to be booked but have not been). And that the accused, thus pre-victimised via partiality, is not marked out by any riches of rights, per se, but by enormous economic, emotional, and reputational costs that he must bear to save himself even though these costs might not have been his to bear, to begin with.

Ribeiro surely realizes all of the above—which is why he sent out a follow-up public letter—on September 17—to the commissioner of Delhi Police. This letter’s following sentences are worth the reader’s time:

There are doubts in my original open letter which you have not addressed. I realise that it is difficult, indeed impossible, to justify the licence given to the three BJP stalwarts I named – licence to rant, rave and threaten those who are peacefully protesting perceived wrongs. If the speakers were Muslims or Leftists the police would have surely taken them in for sedition!

No matter what anybody says, this 91-year old has got chutzpah and plenty of game; at the very least, he makes the exclamation mark likable all over again.

Background material:

Hindustan Times (September 19, 2020) “Delhi riots: 26 former DGPs respond to Ribeiro’s letter, show support for police” (Downloaded from the following URL on September 27, 2020: https://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi-news/delhi-riots-26-former-dgps-write-respond-to-ribeiro-s-letter-show-support-for-delhi-police/story-i8ly2oUs68wdcP0sa1ZlSP.html)

Joshi, Tejas (September 17, 2020) “‘Impossible to justify license given to three BJP stalwarts’: former top cop Julio Ribeiro to Delhi Police” HWEnglish (Downloaded on September 27, 2020 from the following URL: https://hwnews.in/news/national-news/impossible-justify-license-given-three-bjp-stalwarts-former-top-cop-julio-ribeiro-delhi-police/143987 )

—————. (September 27, 2020) “‘Served party for 40 years, is this the reward I get?’: Bengal BJP leader Rahul Sinha irked” HWEnglish (Downloaded from the following URL on September 27, 2020: https://hwnews.in/news/national-news/served-party-40-years-reward-get-bengal-bjp-leader-rahul-sinha-irked/144436 )

Komireddy, Kapil (March 20, 2020) “Modi’s India is racing to a point of no return” Foreign Policy (Downloaded from the following URL on September 27, 2020: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/05/modi-india-delhi-protests/ )

Krishnan, Revathi (September 14, 2020) “9 ex-IPS officers ask Delhi top cop for re-investigation of all riots cases ‘without bias’” The Print (Downloaded from the following URL on September 27, 2020: https://theprint.in/india/9-ex-ips-officers-ask-delhi-top-cop-for-re-investigation-of-all-riots-cases-without-bias/502699/ )

Singh, Shiv Sahay (September 24, 2020) “Mamata Banerjee doubles dole to Durga Puja committees” The Hindu (Downloaded from the following URL on September 28, 2020: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/mamata-banerjee-doubles-dole-to-durga-puja-committees/article32689499.ece)

Singh, Tavleen (September 27, 2020) “‘Reporters’ were so drunk with their power to smear Bollywood’s biggest stars that they failed to fulfil their primary role” The Indian Express (Downloaded from the following URL on September 28, 2020: https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/ncb-bollywood-drugs-case-actors-tavleen-singh-6617262/)

Swaroop, Vijay (September 26, 2020) “Former Bihar DGP Gupteshwar Pandey meets Nitish Kumar, may join JD(U) in run-up to polls” The Hindustan Times (Downloaded from the following URL on September 26, 2020: https://www.hindustantimes.com/bihar-election/former-bihar-dgp-gupteshwar-pandey-meets-nitish-kumar-may-join-jd-u-in-run-up-to-polls/story-frQjVI1htuESkoAZPiofPK.html)

Vaz, J. Clement (1997) Profiles of Eminent Goans: Past and Present (Concept Publishing Company: Delhi), p. 295.

Piyush Mathur, Ph.D., is the author of Technological Forms and Ecological Communication: A Theoretical Heuristic (Lexington Books, 2017).