Artificial Intelligence, history, and the fragility of truth: Reflections after a conversation with Thai artist Nanut Thanapornrapee

by Marcus Brand

Editorial note: In this essay, Marcus Brand reports on Nanut Thanapornrapee’s openly creative AI-enabled historical reconstructions, before delving deeper into the possible adverse effects of AI on actual historiography and historical accountability. Highlighting the broader South-East Asian context of Thanapornrapee’s work, Brand concludes the essay by refusing to regard ‘historical pluralism’ as necessarily democratizing in the real world, and by suggesting some overlooked pointers toward AI regulation.

Enterprising readers may wish to read Ashis Nandy’s academic article ‘History’s Forgotten Doubles’ (1995) for a deeper context to a key dimension of Brand’s reflections here.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming how societies remember, narrate, and contest their past. While much of the public debate focusses on efficiency, innovation, and economic disruption, far less attention is paid to how AI reshapes historical consciousness, political memory, and the foundations on which democratic societies rest.

A recent conversation with Thai artist Nanut Thanapornrapee brought these questions into sharp focus for me. Encountering his work This History Is Auto-Generated: History Bureau Agent (2022) at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, and later discussing his practice in depth, forced me to confront both the creative potential and the democratic risks of AI-enabled history-making.

Our exchange revealed not only shared concerns but also a productive tension between ethical restraint and creative freedom in the age of AI.

AI as an author and bureaucrat of history

Nanut’s This History Is Auto-Generated: History Bureau Agent is a 7-minute, single-channel video work generated using GPT-3 and a database of Thai political memory. The project simulates Thailand’s political history as if it were produced by a hidden bureaucratic apparatus, a ‘history bureau’ charged with generating, editing, and controlling collective memory.

The algorithm is not presented as neutral. It is portrayed as an institutional actor, quietly authoring reality.

The work becomes even more layered through its material presentation. Rather than projecting the film onto a conventional screen, Nanut uses recycled Indonesian textiles, which have been cut, rewoven, and repurposed. The fabric functions as both projection surface and metaphor. Just as the textiles have been recycled into new forms, historical narratives are shredded, recomposed, and repurposed to serve new political ends.

This material choice matters. It reminds the viewer that history does not simply exist. It is processed, filtered, and reassembled. AI, in this sense, is not an abstract technology but a continuation of bureaucratic power by other means.

Western data, non-Western histories

Nanut is acutely aware that most contemporary AI systems are trained predominantly on Western, English-language datasets. This shapes not only the outputs of AI, but also its assumptions about causality, progress, and political legitimacy.

In his early AI experiments (circa 2020–2021), before today’s guardrails and content moderation, Nanut encountered outputs that were politically incorrect, extreme, and unsettling. Rather than treating this as a flaw to be corrected, he treated it as evidence: proof that AI systems expose the biases, exclusions, and ideological defaults embedded in their training data.

For an artist working with Thai political history, this mattered deeply. When AI rewrites non-Western histories through Western-trained models, it does not simply translate; it reframes. Power asymmetries are reproduced at the level of narrative logic.

Nanut’s response is not to purify AI or make it ‘accurate’, but to foreground its distortions, to make the viewer aware that what they are seeing is not history, but a machine-mediated reconstruction shaped by power inequalities.

History as play, mutation, and fiction

Nanut is explicit that he does not consider himself a historian. His practice is research-based, but deliberately non-academic. He reads existing historical research, political testimony, and archival material, then recomposes them through fiction, speculation, and metaphor.

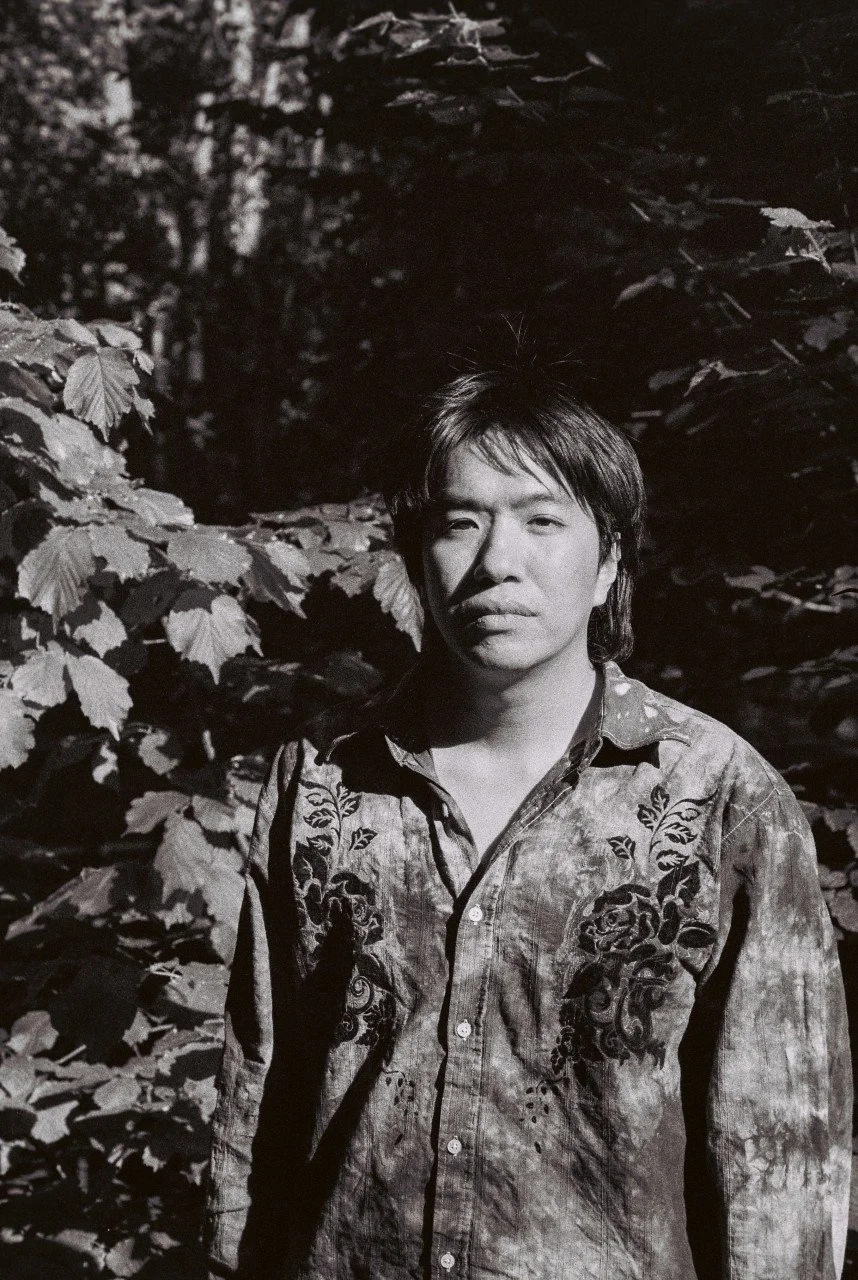

Nanut Thanapornrapee

A recurring theme in his work is that history in Thailand is treated as sacred, especially narratives tied to monarchy, nationalism, and state ideology. These stories are internalized from childhood through rituals, education, and propaganda. Questioning them is not merely controversial; it can feel destabilizing or even dangerous.

Nanut’s strategy is not frontal confrontation. Instead, he plays with history.

One project discussed in our conversation reinterprets the historical episode of King Mongkut’s mid-19th century prediction of a solar eclipse. Using the Saros eclipse cycle (which repeats roughly every 18 years), Nanut constructs a speculative, fictional timeline in which royal power reappears cyclically, vampirically, across centuries. The king becomes an immortal figure whose influence resurfaces again and again, controlling history from the shadows.

This blending of astrophysical accuracy, historical fact, and speculative fiction allows Nanut to ask questions that would be politically difficult to pose directly: How does authority reproduce itself? Why does history feel repetitive? Who benefits from cyclical narratives of power?

The goal is not to deceive, but to destabilize reverence, to remind viewers that history is constructed, mutable, and open to reinterpretation.

Imagination as political capacity

One of Nanut’s most striking insights is his belief that late capitalism and authoritarian cultures have narrowed our capacity to imagine alternative realities. We are trained to accept existing political and economic arrangements as inevitable.

AI, paradoxically, becomes a tool to break this mental enclosure. Even when its outputs are illogical or impractical, they reopen the question of possibility. They allow people to see that the present order is not the only conceivable one.

In this sense, AI becomes an imaginative prosthetic device, an artificial limb as it were, not because it is truthful, but because it disrupts certainty.

This is also why Nanut has increasingly turned to video games as a creative medium. Games do not merely tell stories: they grant agency. Players choose paths, remember or forget, accept or resist narratives.

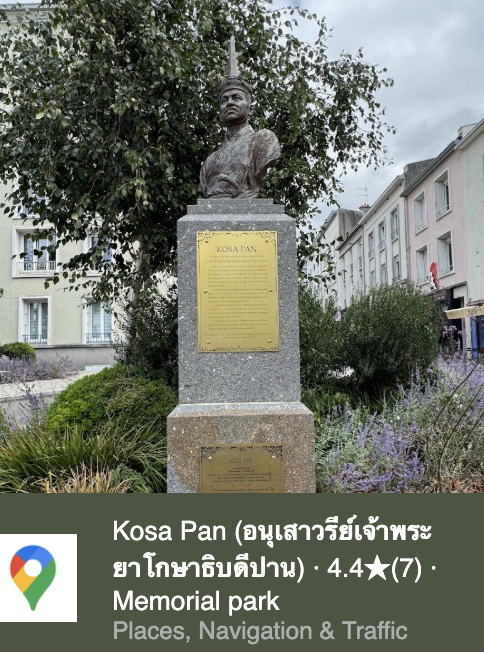

One of his current projects is inspired by a real incident in France. In Brest, there is a statue of Kosa Pan, the first Siamese Ambassador to France, sent by King Narai the Great to King Louis XIV of France in 1686. The bust, erected in 2020, briefly disappeared and reappeared overnight, seemingly turned in a different direction. In Nanut’s game, the player inhabits the statue itself, a former ambassador who comes to life with no memory of who he is.

Memory becomes a resource. Forgetting becomes a choice. Identity is reconstructed through interaction rather than inheritance.

Where my concerns begin

Coming from a background in constitutional law, human rights, and truth-seeking processes, I find Nanut’s work both compelling and unsettling.

In my recent work with a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we confronted a hard truth: without some shared commitment to evidence, context, and responsibility, truth processes collapse. AI already strains this fragile equilibrium.

What concerns me is not fictional history in creative works. Societies have always lived with myths, legends, and historical imagination. The danger lies in AI-enabled historical fragmentation at scale, where every political group can generate its own internally coherent version of the past, reinforce grievances, and reject all others as fabrications.

In Southeast Asia, these dynamics have real consequences. Competing historical narratives continue to fuel tensions between Thailand and Cambodia and deepen ethnic conflict in Myanmar.

Victimhood narratives, often centuries old, are mobilized today to justify exclusion, repression, and violence.

AI does not invent these narratives. But it accelerates them, amplifies them, and makes them harder to contest.

How AI might fuel narratives and identities that foster conflict in South-East Asia

These days, there is a real and measurable trend in how recent Thailand–Cambodia tensions are shaping national narratives, cultural heritage claims, education, and public memory on both sides, especially around heritage sites, identities, and historic traditions. These shifts are part of a broader interplay of politics, nationalism, and historiography.

The longstanding territorial and historical dispute between Thailand and Cambodia isn’t just about land, it’s about the symbolic meanings of that land and its history. Ancient temples such as Preah Vihear and other Angkor-era sites are central claims in these disputes. Both nations view them as foundational to their civilizational identity.

These disputes have repeatedly flared into military clashes and diplomatic crises, with periods of intense fighting (notably in recent months) linked directly to assertions of sovereignty and historic legitimacy, including control of culturally important and revered sites.

The weaponisation of cultural heritage, where heritage itself becomes part of the political and military standoff, has become increasingly visible. Temples have been closed, militarized, or damaged in the conflict zones. In some instances, statues and revered artifacts in contested areas have been removed or destroyed in the course of clashes, sparking political outrage and accusations of disrespect toward cultural legacies.

The UNESCO and other such organisations have repeatedly warned that heritage sites are at risk, underscoring how border tensions directly threaten both countries’ shared past.

There has been a historical trend inside Thailand of downplaying or reframing the influence of the Khmer Empire on what is presented as Thai civilization. Some experts argue that Thai nation-building narratives have purposefully recast or minimized Khmer cultural contributions to Thai language, arts, architecture, and tradition, sometimes depicting them as lesser or peripheral influences.

This includes a linguistic and educational tendency to distinguish the Khmer from the so-called ‘Khom’, even where many historians recognize they refer to the same broader cultural group, a differentiation that simplifies or obscures historical interconnections. Critics describe this process as part of an ideological project to promote a unified Thai identity (‘Thainess’) that leans away from acknowledging deep Khmer roots.

Kosa Pan’s bust in Brest, France

(Image credit: Google Maps)

Cambodian narratives increasingly emphasize the Khmer Empire’s primacy, especially in cultural achievements and stewardship of border temples. In official media and commentary, historic temples and heritage are framed as central to national identity and dignity, not only as tourist attractions.

Cambodian responses to Thai actions around disputed temples are often vocal in framing these as not merely territorial but cultural violations, reflecting how entwined these structures are with modern Cambodian national sentiment.

While official curricular details vary by time and source, there is broad academic and public commentary, especially from outside Thailand, noting that Thai history education typically minimized Khmer influence on early Thai polities, rebranded Khmer architectural and artistic motifs as ‘Thai,’ and treated ancient Angkorian legacies as elements subsumed into later Thai kingdoms rather than acknowledging them as distinct cultural achievements. This narrative strategy, whether entirely state-directed or a product of long-standing nationalist historiography, fits a larger pattern where cultural heritage becomes territorialized in national education.

Public discourse on social media and in mainstream debates reflects this tension and contestation over history, identity, and heritage. Among Thais and Cambodians alike, heated discussions often centre on who ‘owns’ what cultural traditions and whether teaching should reflect shared histories or distinct national identities. In times of heightened conflict, such debates intensify, sometimes leading both publics to view history as something to defend as fiercely as territory.

National storytelling is increasingly zero-sum: Claiming heritage as exclusively Thai or exclusively Khmer often supports territorial claims or legitimizes political positions. Educational and cultural institutions reflect these narratives: Textbooks, museum exhibits, and public history campaigns tend to emphasize each country’s own lineage while downplaying shared or contested legacies. Military clashes, bans on content, and diplomatic stand-offs feed back into cultural narratives, hardening perceptions and framing history as part of a broader contest for identity and sovereignty.

These evolving narratives don’t just affect diplomacy, they shape how citizens understand their past and their neighbour, influence tourism and heritage preservation, and impact how future generations learn about Southeast Asia’s shared but contested histories.

Whose history is it? And who has the power to tell it?

The relevance of Nanut’s experiments in AI historiography and historical fiction becomes especially clear when situated against contemporary disputes over cultural heritage and historical ownership, such as those between Thailand and Cambodia. These conflicts are not merely territorial but epistemic: they concern who may legitimately claim continuity with past civilizations, who names temples and traditions, and how cultural lineages are narrated in museums, education, and public memory. In such contexts, history already operates as a zero-sum resource, where acknowledgment of shared or entangled pasts is often perceived as a political concession. AI enters this landscape not as a neutral mediator but as a powerful amplifier of existing narrative asymmetries.

What distinguishes AI-driven historiography from earlier nationalist revisionism is not its capacity to fabricate false histories, but its ability to generate multiple, internally coherent historical trajectories at scale. By selectively weighting sources, naming conventions, and interpretive frames, AI systems can produce plausible narratives that emphasize uninterrupted civilizational continuity, marginalize inconvenient influences, or reframe contested heritage as naturally belonging to one lineage rather than another. In regions where datasets themselves are shaped by nationalist curation, such as the soft erasure of Khmer attribution in Thai museum displays, these outputs acquire the appearance of objectivity, transforming political exclusions into algorithmic consensus.

Nanut’s work is significant precisely because it foregrounds this shift from disciplinary history toward what might be called imaginative historiography. Rather than asking only what happened, AI enables the systematic exploration of what could have happened and, by extension, what might legitimately be claimed in the present. This capacity aligns uncomfortably well with contemporary heritage disputes, where counterfactual continuity often functions as a substitute for shared history. AI-generated narratives do not need to assert overt falsehoods; they merely need to present one among many plausible pasts as sufficient, coherent, and self-contained.

The danger, as Nanut implicitly demonstrates, lies not in narrative plurality per se but in the loss of historical entanglement. Khmer–Thai history, like much of Southeast Asia’s past, resists clean ontologies: languages, rituals, creative forms, and political authority circulated across polities and centuries in ways that defy modern borders. AI systems, however, are structurally inclined toward clarity, categorization, and ownership. When deployed uncritically in historiography, education, or cultural representation, they risk converting shared pasts into parallel algorithmic realities: distinct, incompatible, and increasingly insulated from dialogue.

In this sense, Nanut’s experiments do not simply illustrate the creative possibilities of AI historical fiction; they function as a cautionary mirror. They reveal how easily AI can stabilize imagined pasts into authoritative narratives, and how quickly these narratives can be mobilized within contemporary struggles over identity, heritage, and legitimacy. The Thai–Cambodian case underscores that the future of AI historiography will be shaped less by technical capacity than by the political and cultural conditions under which historical imagination is permitted to operate.

Creativity, ethics, and responsibility

Here lies the productive tension between Nanut’s practice and my own concerns. Nanut emphasizes play, fiction, and imaginative disruption as ways to loosen authoritarian certainty. I emphasize ethical guardrails, transparency, and responsibility, particularly when AI is applied to truth-telling, historical documentation, and democratic processes. These positions are not contradictory. They operate in different registers. Imaginative works can afford ambiguity. Democratic institutions often cannot.

Yet Nanut’s work performs a crucial function: it acts as an early warning system. Imaginative creativity encounters the ethical and political implications of AI long before they appear in legislation, court cases, or policy frameworks.

His work makes visible what AI governance debates often obscure, that the real struggle is not between truth and fiction, but between power and accountability.

Key takeaways

For me, several insights emerge from my exchange with Nanut:

AI reshapes historical imagination, not just historical knowledge.

Its political impact lies in what it makes thinkable.

2. Historical pluralism is not inherently democratic and conducive to social cohesion.

Without shared reference points, it can fracture and divide societies.

3. ‘Artists’ are often first responders to technological change.

Their work surfaces dilemmas before institutions can name them.

4. The core issue is narrative authority.

Who controls the production of memory, and under what constraints?

5. AI governance must engage culture, not only regulation.

Legal frameworks alone cannot address how people emotionally relate to history and identity.

Conclusion: holding the line

AI places us in an uncomfortable position. It expands imagination while undermining shared reality. It democratizes storytelling while empowering manipulation. It promises insight while eroding trust. The task ahead is not to suppress imagination, nor to freeze history into official narratives. It is to hold the line between creative freedom and democratic responsibility, a line that will necessarily look different in culture, law, museums, and truth commissions. Nanut Thanapornrapee’s work does not offer solutions. But it forces us to confront the question we too often avoid: What kind of historical imagination can democracy survive? That question deserves sustained attention, from creative artists, policymakers, technologists, and human rights practitioners alike.

Marcus Brand, Ph.D, is an expert on international affairs, democratic governance, and constitutional reform, with more than two decades of experience working across Europe, Asia, and the Pacific. Most recently, he served as Chair of Fiji’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

If you wish to contact him, drop us a message via this contact form and we will forward it to him.